Have you ever had a teacher with such a fiery temper that he would throw chalk and blackboard erasers at you if you weren’t paying attention? Ever failed a test and had a teacher scrawl the ‘F’ on the page with such force that it was warm to the touch when he handed it back to you? Ever witnessed a teacher make fun of the school principal in another language in front of students -- and parents?

Mr. Fischer, my grade school French teacher in the early 1980s, did all of these things. Which probably sounds unbelievable, since behavior like this today would earn a teacher a starring role in a trumped up CNN expose on 'Teachers Gone Wild', leaving viewers shaking their heads and fretting about the impact on the children.

Well, it’s true that Mr. Fischer did have an impact on his students -- but it was a positive one. He was youthful, dedicated, energetic, passionate, proud of his culture, and yes, a bit volatile. His teaching methods could best be described as unconventional. You never really knew what would happen in Mr. Fischer’s classroom, and that’s what made it so fun. When it came to teaching us about France, a faraway place we might never see with our own eyes, he had a creative approach that was extremely effective.

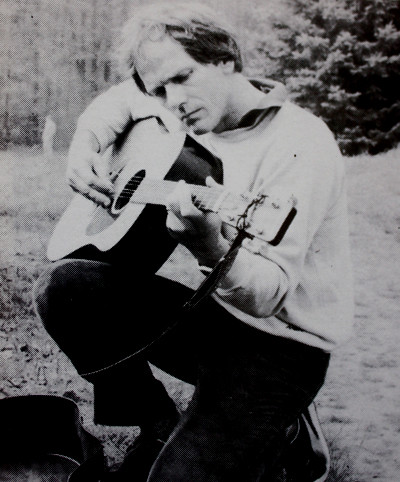

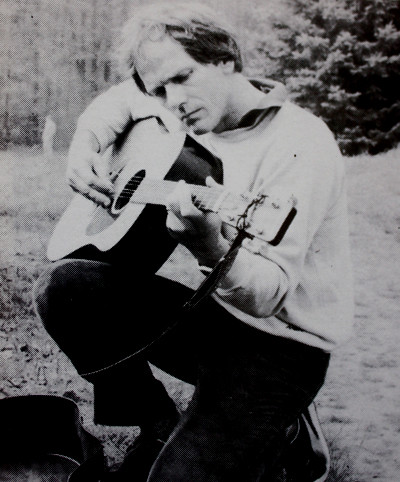

Mr. Fischer was probably in his early thirties when I knew him, thinly built and of average height, with hair that would get longish at times, giving him kind of a wild look. I’m pretty sure he was born in France, but he had lived long enough in the U.S. by that time not to have much of an accent. He also dressed differently than the other teachers at our school, preferring sweaters to button-down shirts. I never saw him wear a tie.

Mr. Fischer had a mischievous side that sometimes made him feel like a co-conspirator against authority. Like the one day when the school principal, Mr. Dunlap, stopped by Mr. Fischer’s class with a group of visiting parents.

We were in the middle of a grammar lesson when Mr. Dunlap strolled unannounced into the classroom, smiled patronizingly at us, and began explaining to the parents that this was where Mr. Fischer dispensed his daily wisdom on French language and culture. Mr. Dunlap inquired as to what we were learning that day, and then asked Mr. Fischer to say something in French for the benefit of the visiting parents.

Mr. Fischer never was a big fan of these sorts of interruptions, which happened regularly. The slightly wicked look on his face as he contemplated Mr. Dunlap’s request seemed to say, “Oh, you want to hear some French? Well, here you go!”

I recall feeling that something memorable was about to happen, and it did.

“Voici Mr. Dunlap. Il est un merde-tete,” Mr. Fischer said with a big, friendly smile.

With that, 25 students clenched their jaws as tightly as they could and fought to suppress their laughter, tears of strain running down their cheeks. Mr. Dunlap nodded to Mr. Fischer and herded the parents to the next classroom. Fortunately, neither he nor the parents understood French, so they had no idea that Mr. Fischer had just called the principal of the school a “shithead”. Once Mr. Dunlap was safely out of earshot, the students erupted.

Classrooms are usually drab, orderly places smelling of wood, old paper, and boredom. Walking into Mr. Fischer’s was an entirely different experience. It hit you right away: the posters of French cities and portraits of famous French people on the walls; the French stamps, coins, bumper stickers, and other paraphernalia laminated into the desktops. There was French music to listen to and French games to play during our free time. It was as if Mr. Fischer had airlifted a smoldering chunk of French culture over to the U.S. and dumped it into his classroom, where it could bathe us all in its glow.

It was here that Mr. Fischer guided his students through the contours of the French language, teaching us about the passé composé, the imparfait, the conditionnel, informal pronouns, dangling participles, and other grammatical nuances. Irregular French verb conjugation has an algebraic complexity to it, and some lessons felt like dentist appointments. Mr. Fischer never coddled his students, though. He had no patience for whining, and if he sensed you weren’t putting enough effort into your studies, you were going to hear about it.

Mr. Fischer graded all of his tests with the same red pen. If you got an ‘A’, he’d write “excellent travail” (great work) on the page, with a friendly penmanship. On the other hand, if you got an ‘F’, he would angrily scribble “Un Desastre!” (a disaster), and his disgust would emanate from the page with all the subtlety of a 20-pound hunk of Limburger cheese. When you did well, Mr. Fischer handed you back you test with a friendly smile; when you didn’t, he would toss it to you as if it had just been used to clean a bird cage.

Mr. Fischer’s teaching style could best be described as asymmetrical; he didn’t just stand in front of the class reading from a book, he would move about the room and present lessons in unique ways. He was like a guerrilla fighter on patrol, hiding in the hills and ducking behind trees, firing shots of learning at his students.

Sometimes, Mr. Fischer would fire actual projectiles at us. One time, he saw me passing a note to a classmate and nailed me directly in the nose with a blackboard eraser heavy with chalk dust. It didn’t hurt, but it was embarrassing, and my classmates sure thought it was funny. With a thick layer of chalk dust coating my face and nostrils, I looked like the Tony Montana in a 7th grade production of Scarface. It took hours for the taste to go away.

Mr. Fischer was a big fan of outside-the-box teaching methods. A couple times every year he would take us on a field trip to his house to cook crepes in the French style. One highlight of these trips was petting Zazzy, his chubby white beagle-mix, who would waddle over to the school grounds every afternoon to check things out.

Mr. Fischer let me bring Watson, my four year old Springer Spaniel, into class one day as part of a class assignment. I was to give a presentation, entirely in French, on how to care for a dog. It was harder than I’d expected, as it required me to speak entirely in French for about 10 minutes straight. But after initial butterflies, I settled in and got it done. Later, my classmates -- and Mr. Fischer himself -- roared in laughter when Watson dropped a deuce in the hallway.

Mr. Fischer never did anything halfway. This was apparent when he accompanied the eighth grade on our annual trip to Camp Susquehanna in the mountainous wilds of northeastern Pennsylvania. As organizer of the class scavenger hunt, Mr. Fischer brought an obvious enthusiasm to the hiding of items, placing them in locations no student would even think of looking. I bet some of the things he hid are still right where he put them.

Mr. Fischer was also really into telling ghost stories around the campfire. The guy could really spin a yarn, and enjoyed making his tales as terrifying as possible by making creative use of noises from the surrounding forest. Rustling leaves, he suggested, were the sounds of skeletons that had clawed their way out of a nearby graveyard to pay us a visit. Tree trunks creaking and groaning in the wind were moans of misery from undead souls lurking nearby.

By the time Mr. Fischer was done telling his tales, I was half-expecting to see a disembodied head floating around the campground. I probably slept about 17 minutes that night.

People that attack life’s challenges instead of shying away from them are usually at home on the ski slopes, and so it was with Mr. Fischer. He led many Saturday school trips to the Poconos, and he was with me the first time I strapped on skis. Just as he was in the classroom, Mr. Fischer had a way of motivating you on the slopes when you thought the going was getting too rough.

Later that day, which included several high-speed encounters between my face and the packed powder of the bunny slope, I was taking off my skis outside the lodge and Mr. Fischer skied up.

"What are you doing? There’s still a half-hour left!" he shouted at me through his ski mask.

Mr. Fischer pointed to the top of the mountain, barely visible through the fog and falling snow, at a tiny strip of white meandering down the side. “Let’s go, I’m taking you down an intermediate trail.”

I’d been hoping to quit while I was ahead. But Mr. Fischer wasn’t having any of that. He was always pushing his students to be better, inside and outside the classroom. To reach down within ourselves and get over whatever obstacle stood in our way. So I put my skis back on and skied that trail with him, and at the end I was glad I’d done it, even though I ended up collecting several more bruises along the way.

That was Mr. Fischer in a nutshell: He was all about getting his students over the hump. If he had to, he would've strapped us on his back and carried us over. But it never came to that, because he always insisted that we get through the difficulty on our own.

Mr. Fischer was all about challenging his students, laying down the tough love, and making us into smarter, stronger people than we were before we first ventured into his classroom. And on all of these counts, I'd say he was a success.